It’s not often I get a phone call from someone I haven’t heard from in more than 50 years. So when my long-lost high school pal, Zipper Wyckoff, said, “Never mind how I managed to track you down, we need to talk,” I was thrown for a loop. So much so that before I could offer some pithy reply like, “So talk already,” he was talking already. Just like that. No pleasantries. No you’ll never guess who this is. He just plunged into it as if we’d hung moments ago and he’d called back because he’d forgotten to tell me one more thing.

“You’re the only person I can discuss this with,” he said. “And I trust we can speak in complete confidence, because you know things about me no one else does, and vice-versa, and I’ve always looked to you as someone in whom I could confide, and know I still can. Right?”

“Of course,” I said, dutifully.

Here I will pause to provide a highly selective and admittedly superficial account of the person with whom I was about to converse, as he existed in my hastily recalled, if well curated experience of him, some 52 years earlier.

Zipper Wyckoff was a pudgy, sallow faced sophomore who waddled down the halls of our dorm smoking mentholated cigarettes like an effete Rumanian. He’d suck a toke through pouting fish lips, contemplate the cig while silently rehearsing some obtuse philosophical prescription, and simultaneously exhale and expound. He’d say shit that made no sense. Stuff like, “poverty is the porridge of neglect,” or, “life is a game played on a solid colored chess board.” To label him smarmy was overly generous. Asshole rang true to many. Yet, for reasons entirely unknown to me, women loved him. Drop-dead gorgeous women. Young, eager women. A never-ending stream, thereof.

Needless to say, I was utterly intrigued by Zipper’s technique with women. After many months of dogged observation, I’d come to the conclusion that it was purely a matter of attitude. He just looked at these beautiful girls a certain way, shifting effortlessly into a persona that was part Cary Grant and part Timothy Leary. He once quipped to me, “I can read a woman like a want-ad. First I listen to them, then I tell them what they want.” He called every one of his women “Honey.” And they adored it.

This was a guy who was allergic to muscle tone and possessed the looks of a well-used punching bag. His one distinguishing facial feature consisted of an irregular, cauliflower-shaped growth behind his left earlobe. To look at him, you’d have taken him to be the guy least likely to score with any woman, let alone a parade of goddesses.

In fact, I now recalled that the last time I encountered Zipper was when I, quite miraculously, saw him walking toward me on the Via del Corso, a stunning specimen of womanhood on his arm.

“Ronald!” he said with a smile that lent actual definition to his visage. (By the way, no one called me ‘Ronald’. Only Zipper.) “Ronald, this is Kim. Honey, this is my dear friend, Ronald.”

I said hello to Kim, who responded by clutching onto Zipper all the tighter. Her apparent insecurity struck me as odd, since she looked like she’d just walked off the pages of Vogue. She may as well have been Catherine Deneuve. And that’s the point.

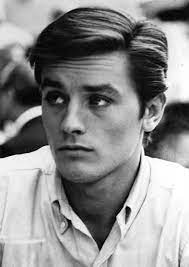

Speaking of which, Zipper said: “Alain Delon is dead.” And then silence.

Supposing it was my turn to say something I said, “You called to tell me Alain Delon is dead?”

“Well, that’s the thing! That’s exactly why I called. That’s what I need to talk to you about.” Zipper was amped up. “Because before you met me, I wasn’t the person you knew. At all. I mean, I was the farthest thing possible from the person you knew. I was…a zero. A nothing. A complete non-entity. Hard to believe, I know. But it’s true. And I was miserable. And I was making other people miserable. So my mother took me to see a shrink.”

Here Zipper paused to take a sip of something and compose himself before resuming at a more measured pace.

“My mother arranged for me to see a very highly regarded therapist in Beverly Hills. Dr. Hyman Gilp. Big-time guy in the field, even though he had his idiosyncrasies. In fact I was immediately suspicious of the guy because I saw that the name on his diplomas was spelled, G – I – L – P – T. But the name on the placard outside his office was just G – I – L – P. He shortened it. But anyway, he spent I don’t know, half an hour, forty-five minutes asking me questions. Did I date? Did I go to high school social events? Did I know how to dance? Did I ever have a girlfriend? Did I feel nervous around females? And so on. And then he asks me to take a seat in the waiting room so he can talk to my mother. And a minute later I hear my mother yelling and screaming. I mean actually yelling and screaming.”

It should be noted here that Leticia (“Letty”) Wyckoff – a piece of work in her own right – was, herself, a therapist. As was Zipper’s father, Sig. (Seriously. His name, however, was Sigfried, and he was big-time. Which, I think, pissed off Letty, who considered herself superior to Sig in all respects.)

Zipper continued. “So we’re driving home and I knew I wouldn’t even need to ask my mother to tell me what the hell went on in there because, as you well know, Ronald, my mother withheld nothing from me.”

He said “withheld” in the past tense, leading me to surmise that Letty Wyckoff had likely met her demise some years ago.

“’I go into the man’s office,’ she says, ‘and he’s scribbling furiously in his notebook. Furiously! And he has the audacity to leave me sitting there while he’s scribbling. So I get up and walk to the side of his desk to see what he’s writing, which obviously disturbed him. So he looks up at me and asks what I’m doing. And I could see that he had scribbled the letters S – R – C in large block print. Very large block print, which he had underlined several times. So I asked him: What is S – R – C?’ That’s what my mother asked. What is S – R – C?”

“What is S – R – C?” I asked?

“This is humiliating,” Zipper says. “Humiliating. Dr. Gilp tells my mother S – R – C is a personal notation for the condition he thinks I have. And my mother says: ‘And what, pray tell, does S – R – C stand for? Please do me the professional courtesy of unpacking it for me.’ And Dr. Gilp obliges. He tells her…” Zipper’s voice trails off. He’s choked up. “He tells her it stands for Sub-Rachmones Case. And my mother gets pissed. Really pissed off. She starts yelling at him: ‘Sub-Rachmones Case!? Are you fucking kidding me? You’ve got the DSM sitting there in front of you and you diagnose my son as a Sub-Rachmones Case?’ And she storms out of there and tells me all of this on the way home.”

I really didn’t know what to say. I was wondering what happened to Alain Delon, and was about to find out.

“The next week she takes me back to Dr. Gilp. Can you believe it? After all the sturm und drang (one of Zipper’s favorite expressions) she hauls me back to Dr. Gilp’s office, and it was like nothing out of the ordinary had ever happened between them. And so I began seeing him on a regular basis and you know what? He wasn’t a bad guy. He was dealing with some stuff of his own. I mean, I think he was going through the process of changing his own orientation as a therapist, moving away from a traditional Freudian perspective toward a Rational Emotive approach. And I respected that.”

Whatever.

“And as part of his own process,” Zipper continued, suddenly upbeat, “he told me he wanted to try an experiment with me, the experiment being that I was supposed to imagine myself as Alain Delon.”

And there it was!

“I know, right?” (I hadn’t said anything.) “I mean, I’d never even heard of Alain Delon. And when Dr. Gilp showed me a photo I’m like, ‘you’re shitting me, right?’ But he’s like, ‘why not? It’s your mind. You get to decide how you see yourself. What’s the worst that can happen?’”

“Did your mother know?” I asked.

“I told her. And she loved the idea. Loved it! She loved it so much that she wanted Dr. Gilp to hypnotize me into actually believing I was Alain Delon. Can you believe it? But there were ethical considerations and whatnot. So we left it at just imagining myself to be Alain Delon, knowing I really wasn’t him.”

“That’s…incredible,” I said, again not knowing what to say.

“It wasn’t easy,” said Zipper. “It took an immense amount of work on my part. Le Samourai was playing at the Nuart, and I made a point of seeing it four or five times. But Delon is hidden under a trench coat and hat for most of the film, and I wanted to see more of him. And right on cue the Los Feliz screens an earlier film of his, Purple Noon. They ran it for a week and I must have seen it at least 10 times. I told my mother about it and she ended up seeing it three or four times. Even Dr. Gilp went to see it.”

“And then?” I asked.

“And then I was ready. You know the rest. You saw it for yourself. And you always wondered how I did it. I know you did. You always wanted to know how I pulled it off. And now you do.”

“And now he’s gone,” I said, faintly, only faintly understanding why Zipper had called.

“And now he’s gone,” echoed Zipper.

“But we’re still here,” I said.

“It was good to have connected, Ronald.” said Zipper, before he disconnected.

That night while lying in bed I took myself back to my own high school days and imagined what life would have been like if I actually was Alain Delon. I was sitting in my fourth period French class. The most desired girl in the school, Rhonda McCall, was seated four rows and a million miles away. She was perfect in every respect, and perfectly unapproachable. If you weren’t the captain of the varsity football team, or the male lead in this year’s theatrical production, there was no point in trying. She didn’t know I existed. And I couldn’t so much as look at her for fear of facing my abject and irredeemable nothingness.

But now I was Alain Delon. And I could look at anyone I damn well pleased. So I did look at Rhonda McCall. Not with the shameful self-consciousness of a passing glimpse or furtive glance. Not from the fetid dungeon of teenage nothingness. Not this time. Just this once I rose up, walked over to Rhonda McCall and looked down upon her. And when she looked up, my eyes locked on hers, and I smiled as only Alain Delon could.

The effect was devastating. Remember the newsreel footage of the experimental buildings being subjected to the first series of atomic bomb tests in the New Mexican desert? That was pretty much the impact my smile had upon Rhonda McCall. Her resistance disintegrated and she just melted, cupping her hands over her mouth to mute the telltale gasps of involuntary sexual submission that overwhelmed her before she understood what was happening. Boom!

Or maybe not. In the afterglow of my perverse, pretend take-down of Rhonda McCall, it occurred to me that maybe, just maybe, Rhonda was a schlub just like the rest of us. A girl with self-doubts and insecurities of her own who would have welcomed a smile, even if it came from a bottom-feeder like me. And maybe the only thing in need of being blown away was my own bullshit.

In the morning my wife asked me if I was aware that I’d been laughing in my sleep.

“Really?” I said, propping myself up on an elbow and facing her. “Take a look at me, Honey.”

Alain Delon died on August 18, 2024 at the age of 88. I vividly recall the first time I chanced to see the French actor on the screen – a tiny, folding one at that, as I happened to be living on a kibbutz in Israel at the time. The film was “The Sicilian Clan,” a 1969 crime caper that also featured the great Jean Gabin. The movie was actually shot three times with the actors speaking French, Italian, and English in successive takes, rather than simply dubbing a single cut. (Delon never bothered to master English, a decision that likely attenuated his notoriety in the U.S.) “Purple Noon” (Plein Soleil) would eventually be remade as “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” the 1999 drama starring Matt Damon.

Like countless others, I was dumbstruck by Alain Delon’s preternatural good looks. He was simply the most beautiful man I had ever seen. And that probably remains true nearly 55 years later. (I felt likewise when I first set eyes upon Catherine Deneuve in “Belle de Jour.” But I think Alain Delon’s looks were even more striking.)

I’ve watched many of Delon’s movies over the years, some having worn better than others. When it comes to sheer star power, he had it in spades.

1 What can be learned from the fact that the most gorgeous man living, towards the end, asked to have his dog put to sleep and be buried with him?

2 Why didn’t you continue the conversation with Zipper? Aren`t you curious as to why he called you? Did he call others? Did you call him back to tell him about YOUR dream??? Aren`t you curious as to his present life?

3 Whatever happened to Rhonda? Don`t you want to track her down and find out? Or maybe you already have her number in your rolodex????

4 As always, your writing is so entertaining, introspective yet flamboyant. And this is verrrrry sexy. YOU’VE GOT TALENT!!!!